Bodies, Grids and Ecstasy

Düsseldorf

Type

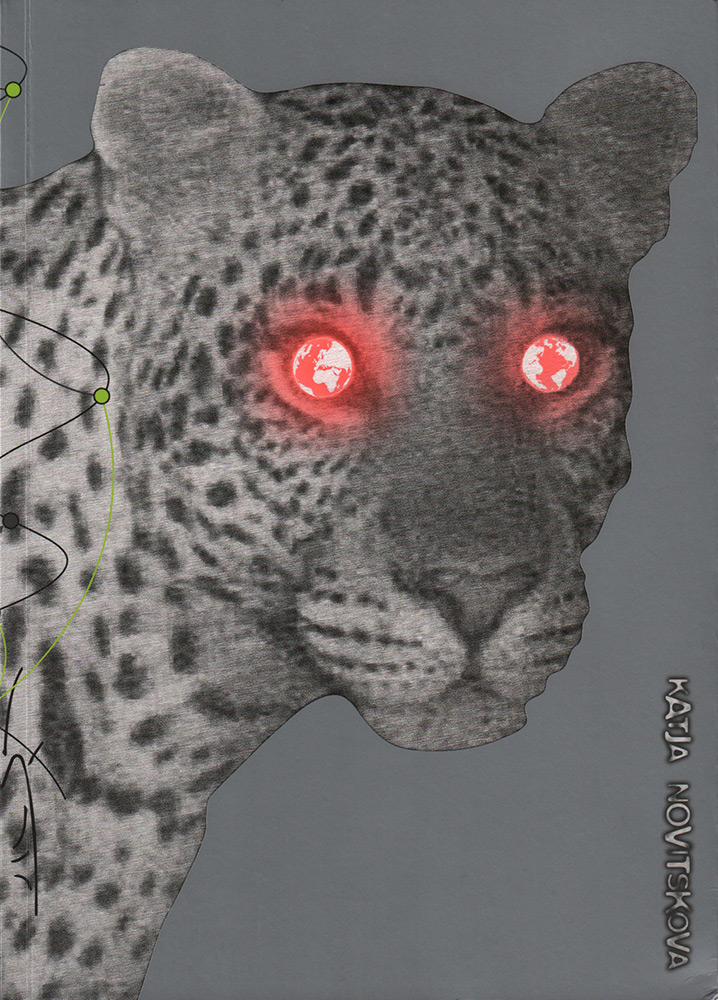

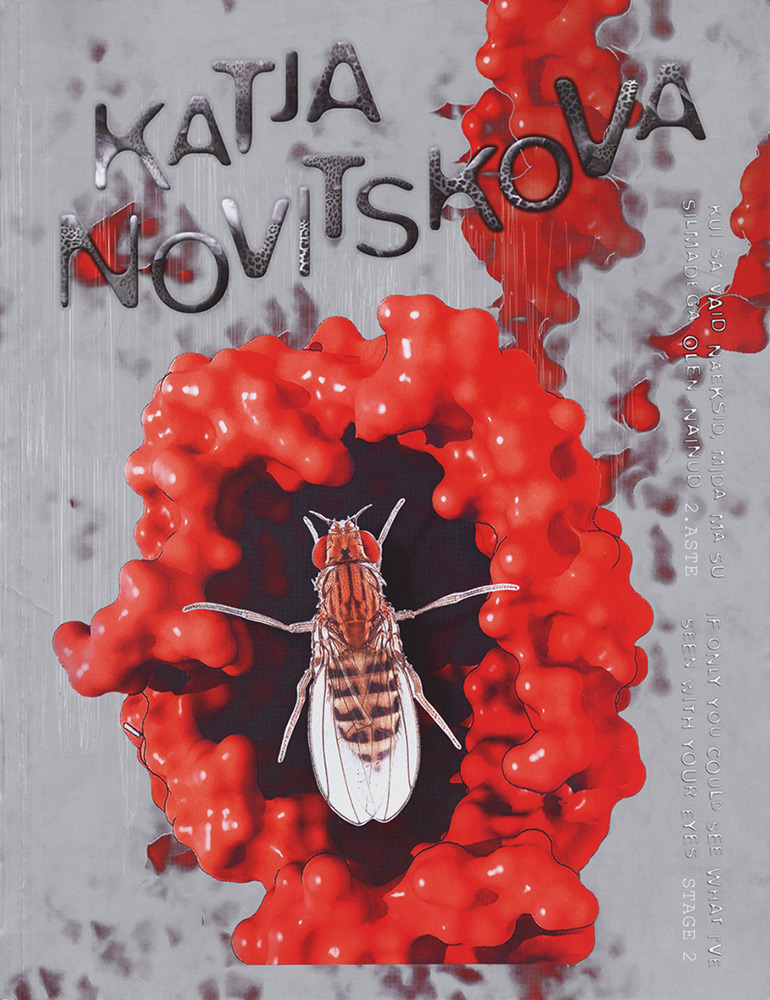

Participating artists: Margret Eicher, Beate Gütschow, Verena Issel, Inna Levinson, Roy Mordechay, Katja Novitskova, Pavel Pepperstein, Pieter Schoolwerth, Lena Schramm

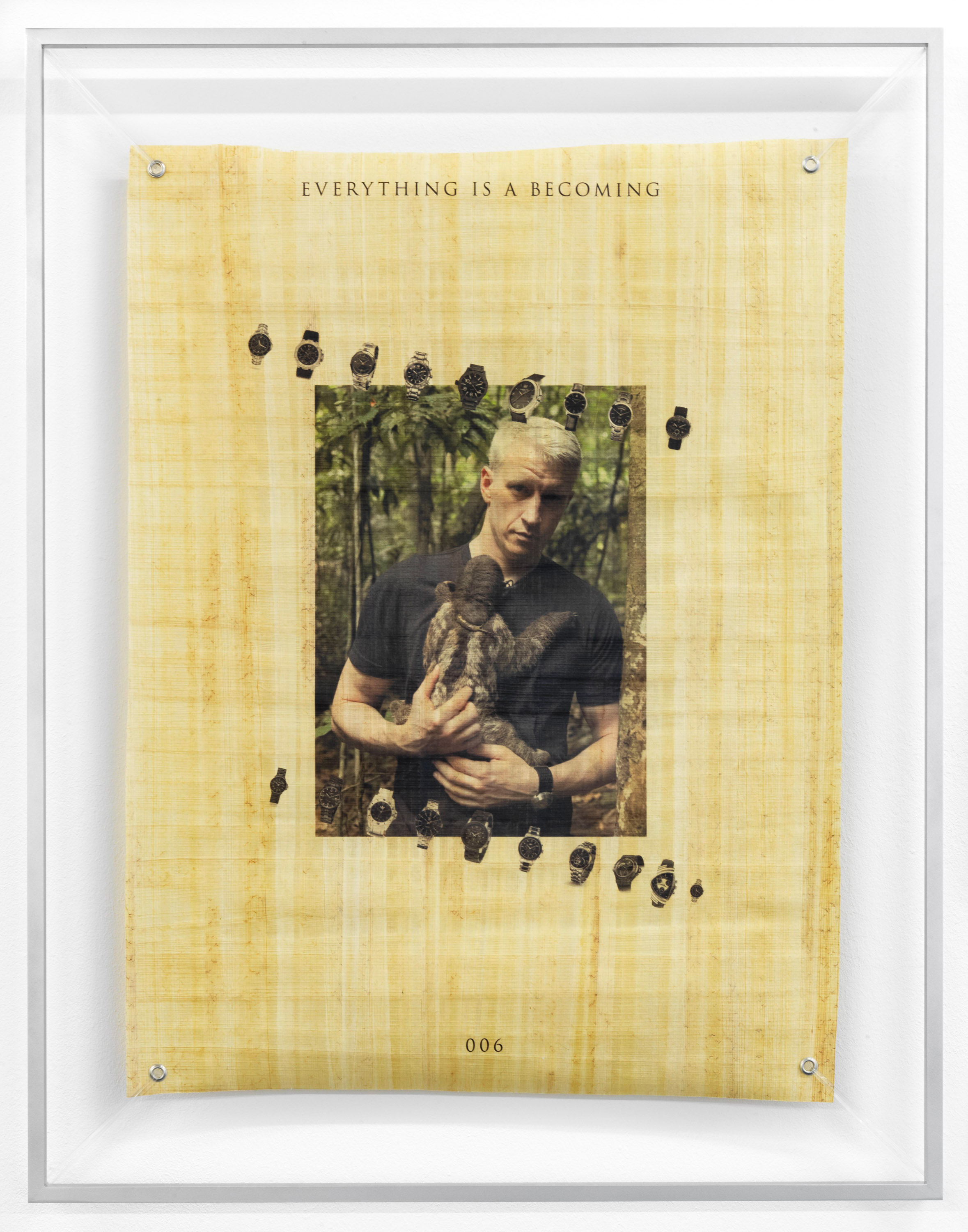

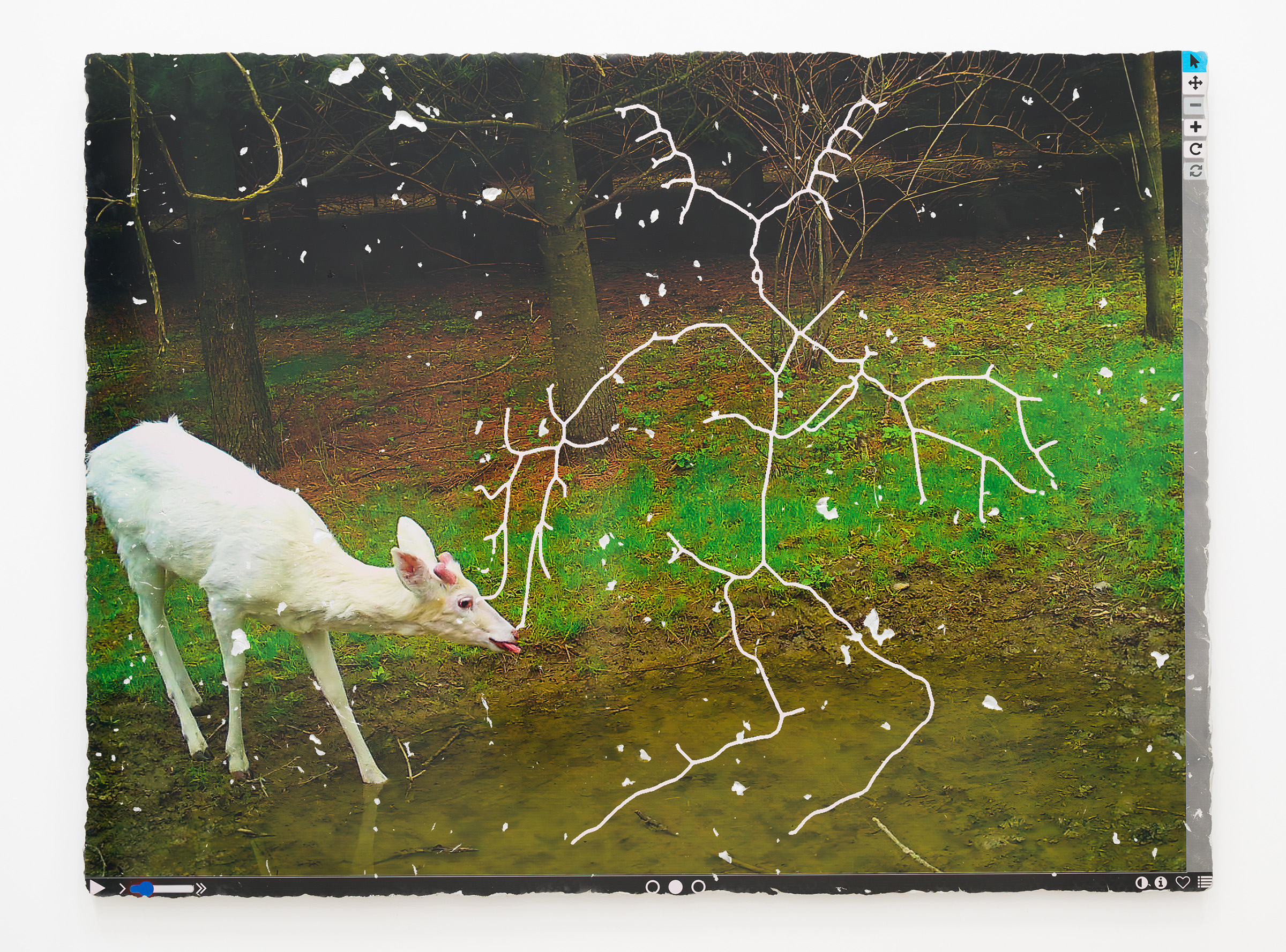

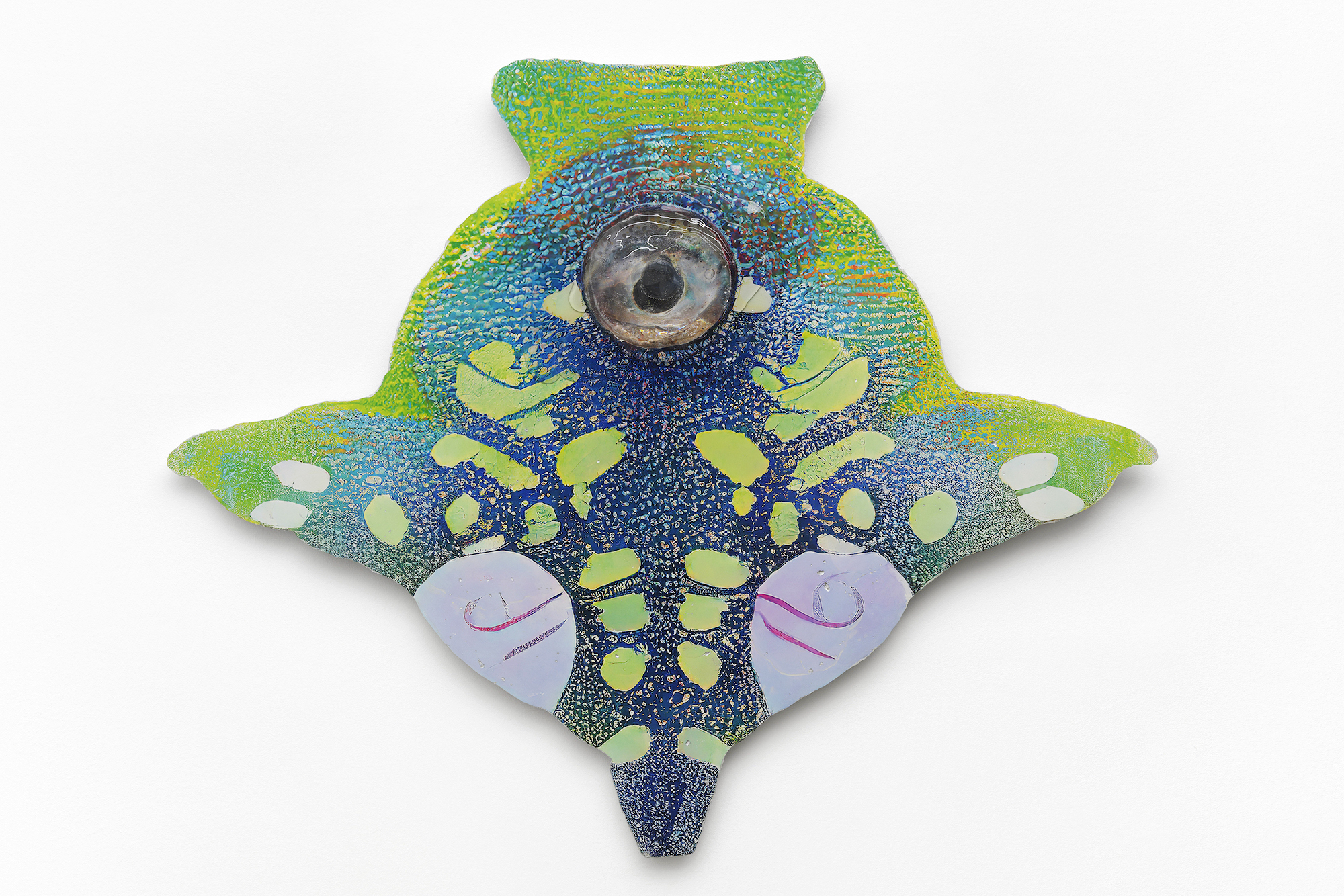

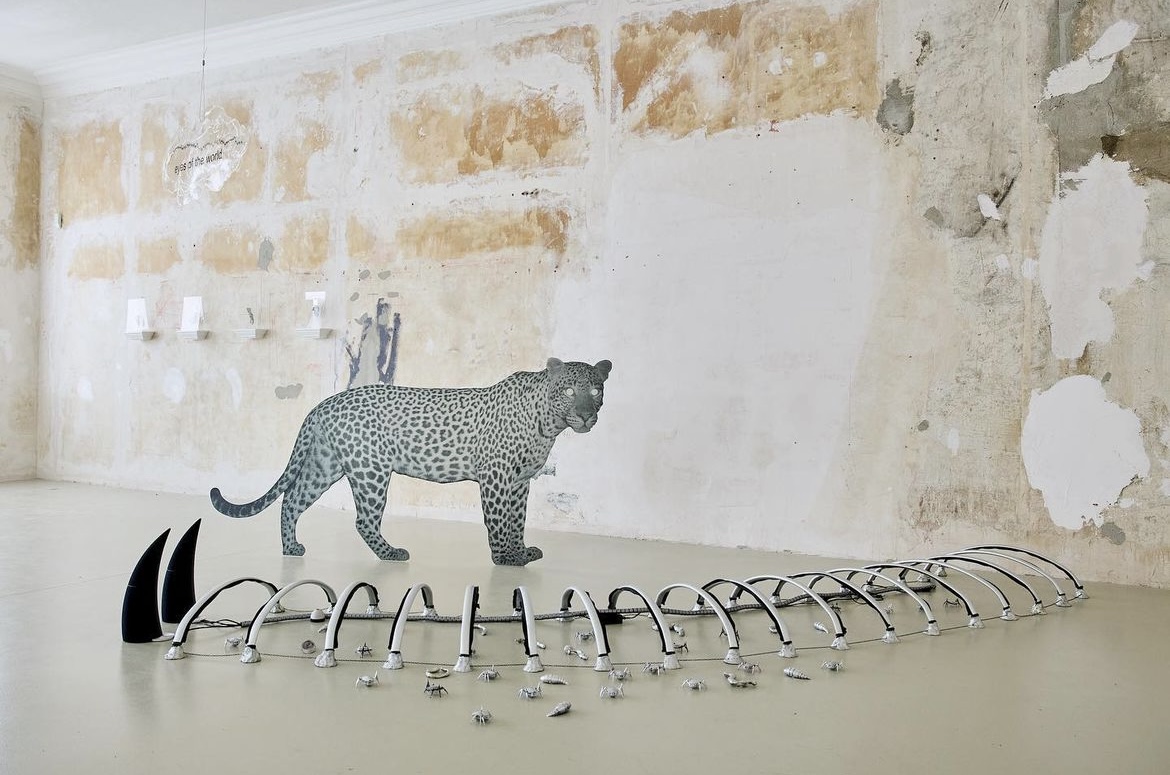

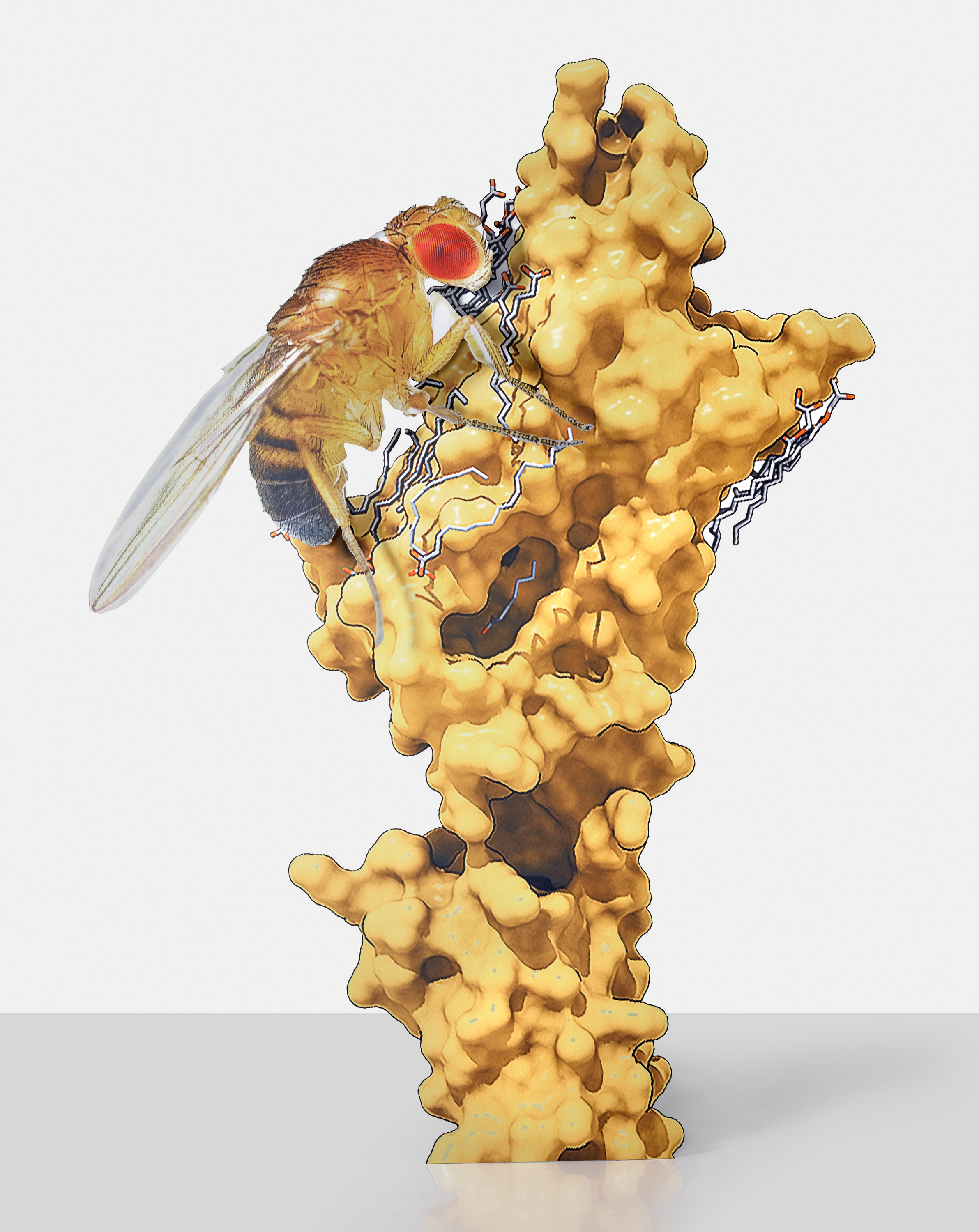

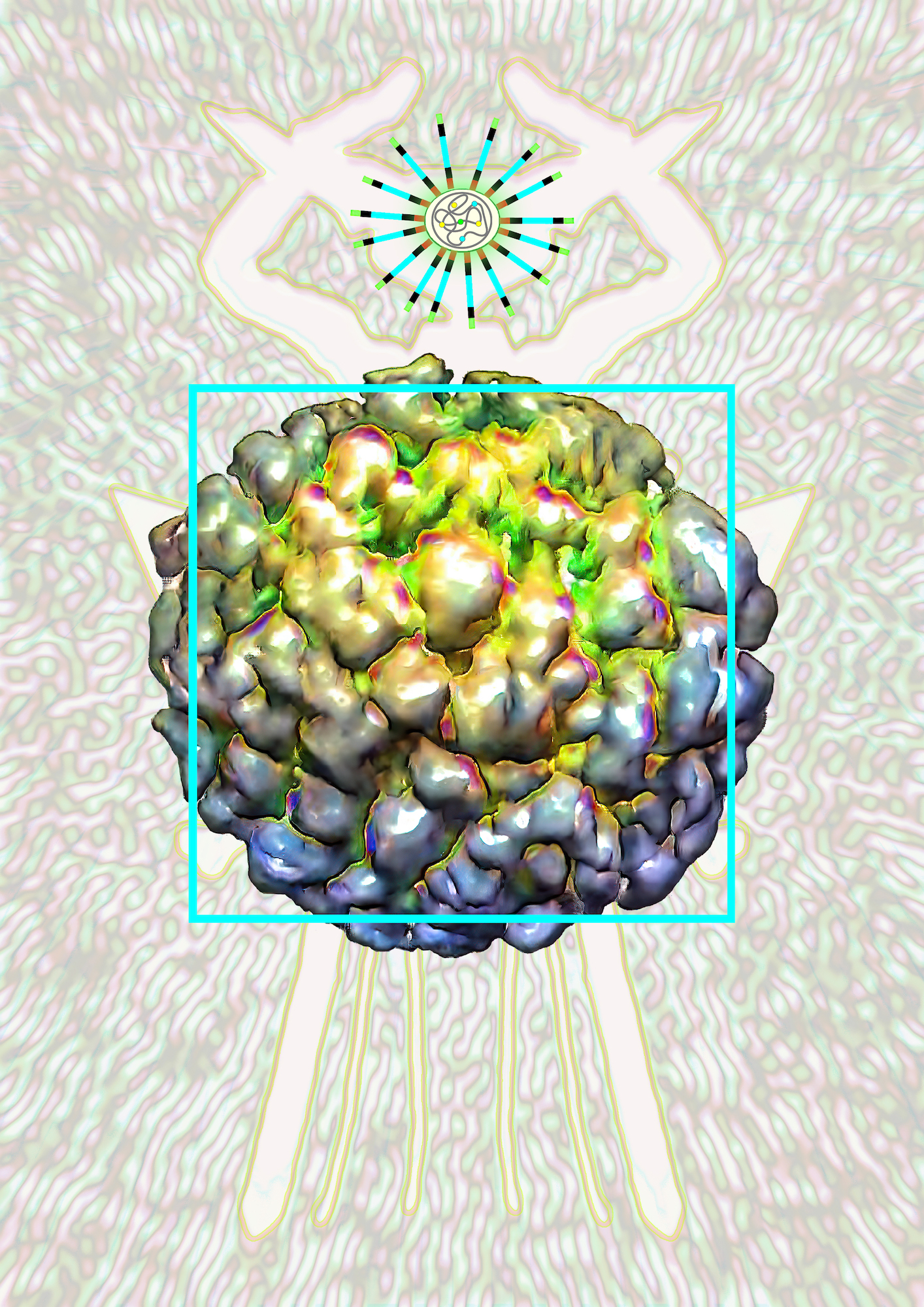

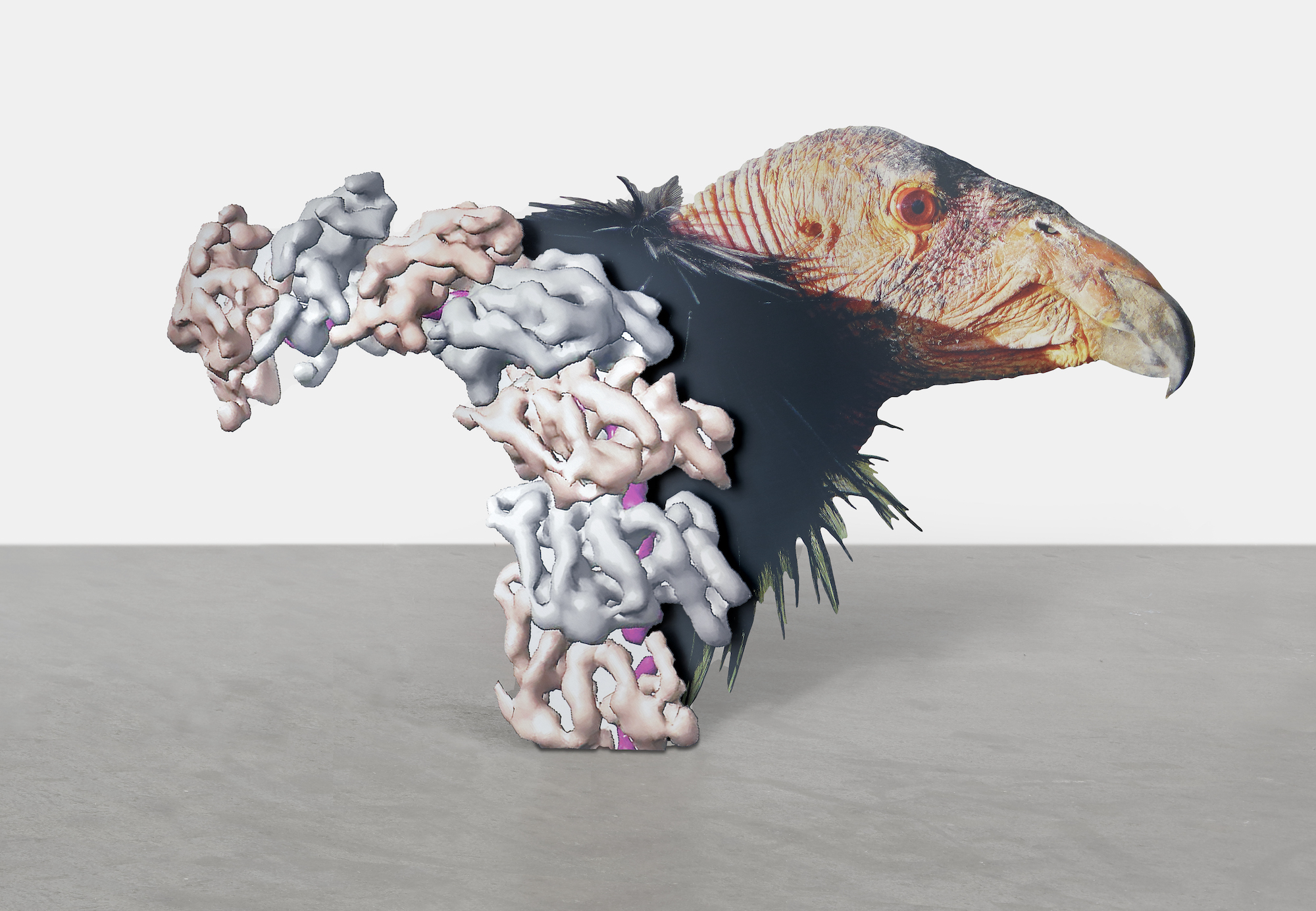

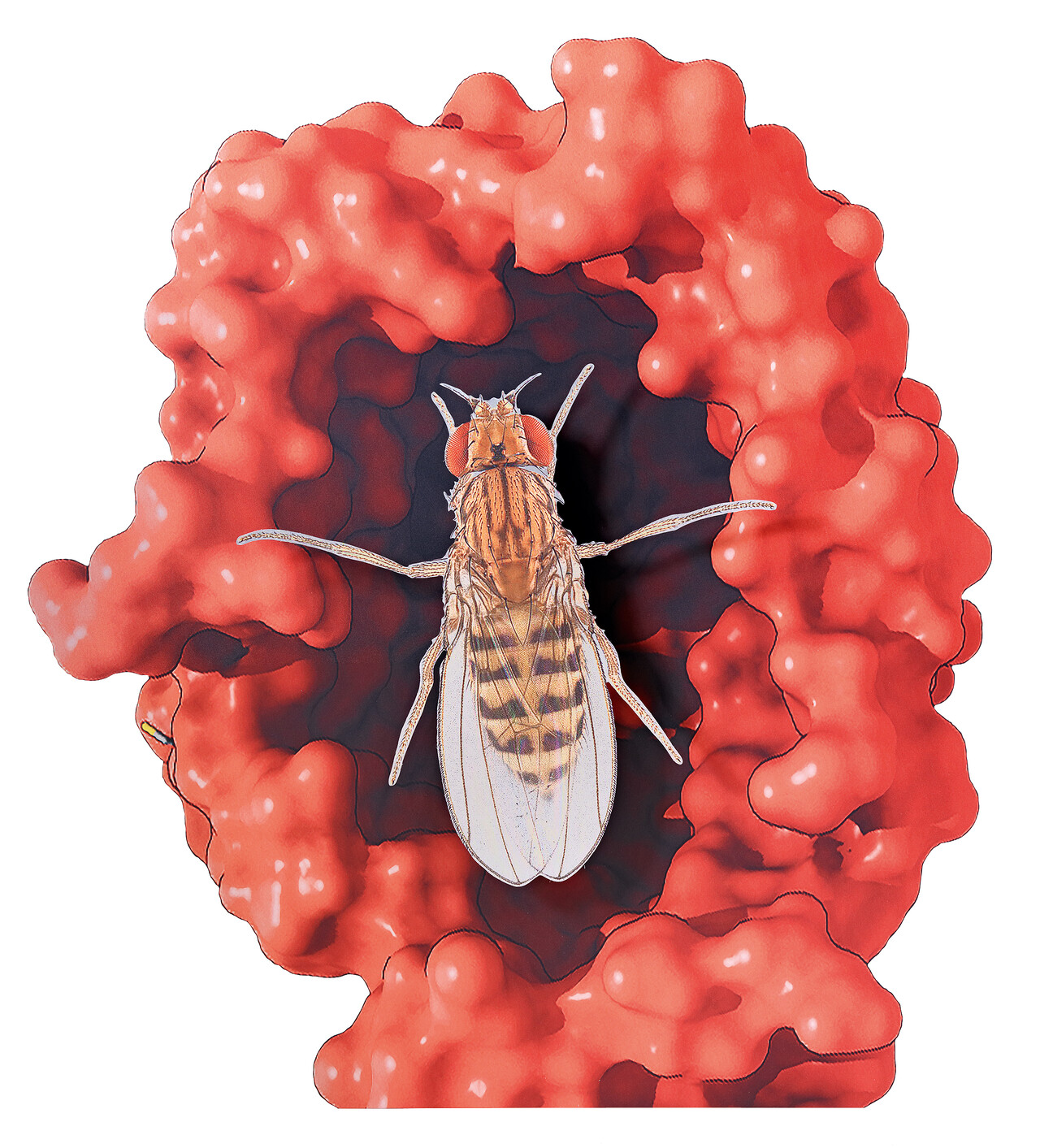

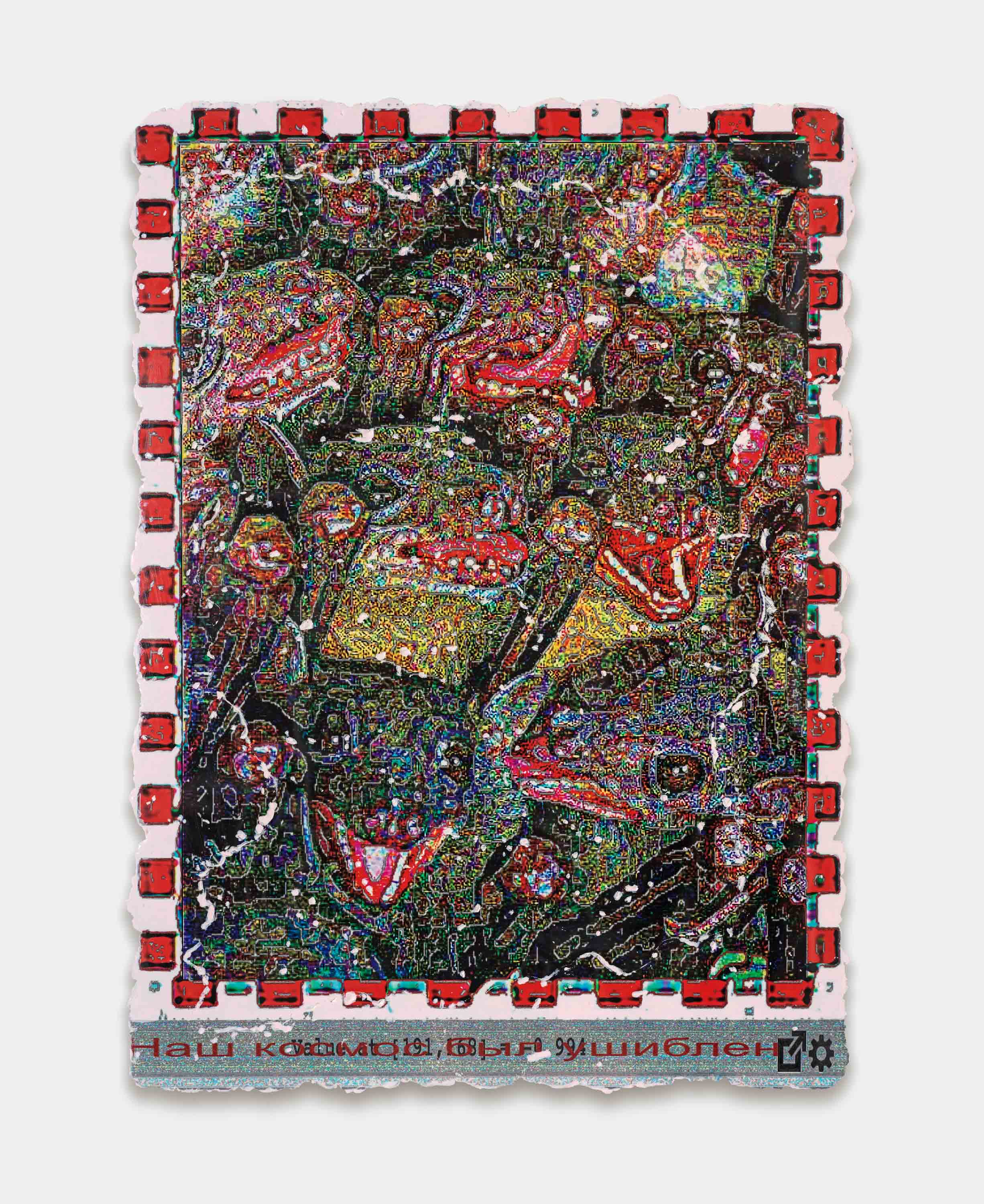

What becomes of physical reality in a world that is increasingly pervaded by digital processes? This question lies at the heart of the group exhibition Bodies, Grids and Ecstasy. The show confronts visitors with surprising encounters and contradictions between surface and space, abstraction and matter, reality and fiction. The show combines images, objects and sculptures in which things come together or are pieced together that as such are not compatible – like collages with invisible seams.

Bodies, Grids and Ecstasy shows a variety of artistic paths that lead away from the two-dimensionality of the gridded flatland back to the world of the haptic, the corporeal and story-telling. Sometimes these paths run in straight lines, be it in unexpected directions, but their course can also be convoluted, humorous and enigmatic, occasionally even issuing critical sideswipes at the political and economic consequences of digitalisation.

The artists in this exhibition make use of digital source material or imaging software, but this is not the kind of art to be experienced solely on a screen or with a VR headset. The works are located in physical space; at the same time, however, they reveal how much our sense of that very space is altered as digitally calculated and simulated phenomena steadily invade our everyday life and living environment.

On multiple levels we are made aware of things and processes that generally escape our conscious perception. The media theorist Marshall McLuhan who, as early as the 1960s, in prediction of the electronic and digital age far-sightedly ventured to write: “the serious artist is the only person able to encounter technology with impunity, just because he is an expert aware of the changes in sense perception.” In other words, artists are able to see what is beyond our horizon – an analogy to our three-dimensional world that lies beyond the comprehension of the inhabitants of the flatland conceived by the English mathematician Edwin A. Abbott in his book Flatland. A Romance of Many Dimensions, published in 1884. Abbott's intention was also to communicate the then much-debated issue of the fourth dimension to lay people with an interest in science. As inhabitants of three-dimensional space, we can perceive this flatland from above. However, those who are at home there are trapped in the horizontal dimension and can barely make out the course of a line the moment it bends around a corner.

A flatland was also envisioned by the radical non-representational art that found orientation not least in the grid patterns of the modern industrial age. The US-American art theorist Rosalind W. Krauss analysed the grid as a model of modern, self-referential works that hold testimony to nothing else but themselves: “Flattened, geometricised, ordered, it is anti-naturalistic, anti-mimetic, anti-real. It is what art looks like when it turns its back on nature.” “The barrier [that the grid] has lowered between the arts of vision and those of language has been almost totally successful in walling the visual arts into a realm of exclusive visuality and defending them against the intrusion of speech.”

For Krauss, the regular pattern of a grid is unaffected by time and immune to further development. Today, by contrast, it stands for the opposite: through contemporary imaging software the grid has become the visual formula for a potential source of infinite variations.

Thus, in contemporary art, the order and calculability of the grid are often no more than a starting point from which things can be made to happen that could not be pre-programmed. This, on the one hand, counterbalances the disembodiment and dematerialisation that issues from digitalisation. On the other hand, even where the human body or physical substance are out of the game, we still have been bequeathed a massive ecological footprint.

To put it bluntly, there is no such thing as abstraction. However much one tries to eradicate them, body and space keep coming back. They then often look unreal and distorted as if witnessed under the influence of drugs. Is the suggestion of three-dimensionality on a plane the only illusion or is twodimensionality likewise a deception? For if it were real, we would have no space to exist. Or does whatever refuses to sit neatly within an algorithmic grid simply become analogue residual matter?

%20detail%204.jpg)

-web.jpg)

-web.jpg)

.JPG)

.jpg)

.jpg)